East Timor Crises, Conflicts and Security

After independence, Timor-Leste was initially considered one of the most successful UN interventions. But the UN’s model child slid into serious crises. Poverty and sluggish economic development fuel frustration and lead to social conflict. Half of the country’s 1.2 million people are under 19 and unemployment among young adults is very high. Some of the young adults organize themselves in gangs or participate in martial arts groups. With the groups, it is about patronage networks that are also intertwined with the country’s political elites. They have a high proportion of members within the armed forces (F-FDTL) and the police (PNTL). A violence subculture has developed within some of these groups. In 2013 the government banned three of the largest martial arts groups. The criminalization, which human rights organizations complain about as unconstitutional, has so far not helped to resolve the conflict.

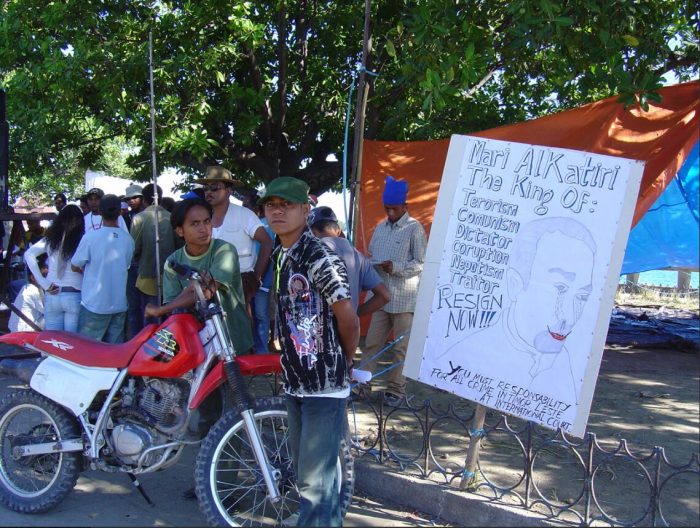

But power struggles in particular within the political elite, combined with the instrumentalization and politicization of the security sector, repeatedly resulted in outbreaks of violence that shook the country. The political crisis of 2006 even brought it to the brink of collapse. Houses burned again in 2004. In 2005 Prime Minister Mari Alkatiri was barely able to hold his ground politically when the Catholic Church mobilized the masses against him. In 2006, parts of the country’s army (the so-called petitinarians) deserted when disputes arose over unequal treatment of people from eastern and western parts of the country. The problem quickly spread across the country. Youth gangs from the East and West attacked each other, Interior Minister Lobato armed civilians, and military units shot at unarmed police officers and neutral UN peacekeepers. Finally, a new international protection force (with the participation of Australia, New Zealand, Malaysia and Portugal) was able to restore a minimum of order and security. In the context of the 2006 crisis, around 150,000 people fled to refugee camps, which dominated the cityscape of the capital for two years. Poverty and disorientation among young people as well as disputes over land ownership are causes and consequences of conflict that are by no means considered to be resolved. The difficult reintegration of the IDPs showed how very old conflicts (proponents of independence vs. pro-Indonesian parts of the population) and new conflicts (FRETILIN vs. AMP) permeated each other socially and party political interests were put above national interests.

According to ehistorylib, the young country was put to a severe test on February 11, 2008, when the fugitive soldiers carried out attacks on President José Ramos-Horta and Prime Minister Xanana Gusmão under unknown circumstances. Ramos-Horta was seriously injured and had to be flown to neighboring Australia. Gusmão was uninjured. Two of the 20 attackers were killed in an exchange of fire with the President’s security forces, including the former commandant of the military police, Major Alfredo Reinado, whose rebel group had significantly destabilized the country for several months. Under the pressure of these events, the insurgents surrendered and gang violence subsided. However, the country’s security problems remain challenging.

Today Timor-Leste has left the crisis years behind. The then President José Ramos-Horta, who was completely committed to restoring national unity and peace, played a major role in this. It was no less important than balancing the deep political divisions, overcoming the rifts in society, and at the same time negotiating the necessary support from the United Nations and international security forces. Since then, many different kinds of peacebuilding measures have been undertaken at the state and civil society level and in development cooperation (see chapter: Potentials of civil conflict management).

The government “bought time and peace” by compensating the refugees and releasing the renegade soldiers into civilian life with compensation. The efforts of the United Nations to reform the security sector have turned out badly than right. It only included the police, not the military, as the government had no interest in it. Not least because of his high authority as a former resistance leader, the then Prime Minister Xanana Gusmão was able to moderate the tensions between the police and the military. He merged the Ministry of Defense and State Security and took over the ministerial post in addition to his position as Prime Minister. “Joint operations”, among other things, served as moderation, but they opened the doors for the military to domestic operations. Reform in the security sector remains a major task. So far, the government has continued to rely on joint operations by the F-FDTL and PNTL to combat illegal groups that contribute to instability. The organization Fundasaun Mahein, who has the security sector in focus, criticizes the operations as bad practice and characterized by political aggressiveness. The government is investing more in war than in peace. It should develop a national security policy that responds appropriately to today’s threats. Amnesty International called for urgent action in May 2015. Dozens of people have been arbitrarily arrested and tortured in Laga and Baguia, Baucau district. The police and military carried out a joint operation there against the former resistance fighter Mauk Moruk and his supporters of the banned Marine Revolutionary Council. Mauk Moruk was fatally injured in an exchange of fire. He counted as an opponent of Xanana Gusmão and had repeatedly called for the resignation of the government and the dissolution of parliament.

It would therefore be premature to classify the escalation potential as low. Conflicts can easily be reignited and often flow into one another. The following conflicts can be identified: youth and gang violence, party-politically motivated violence, flare-up of communal conflicts, violent ex-combatants and an unstable security sector. Violence continues to be a means of asserting interests in everyday life and in political culture. As long as democratic values and methods of civil conflict management have not yet been adequately captured and internalized, the old patterns of behavior, shaped by oppression and resistance, continue to prevail.

But the process of change is palpable: According to a recent survey by the Asia Foundation (April 2016), the population is optimistic about the security situation. Trust in the police has grown and people are increasingly turning to the police for crimes. The local organization BELUN (2017) comes to the conclusion that the police and the military enjoy broad acceptance and legitimacy among the East Timorese population. However, Belun warns that the behavior of staff from both institutions has not yet lived up to public expectations.

Fundasan Mahein calls on the decision-makers of the PNTL to show courageous, visionary leadership in 2019. There is a lack of: “There are no clear guidelines for regulating weapons, deciding on staffing and ensuring uniform training within the police. Due to a lack of political guidelines, it often seems as if PNTL is reacting to the latest problem instead of taking proactive steps to prevent the next one. ”In 2018, the illicit use of service weapons sparked massive protests. In Dili, for example, a drunk police officer shot three young men off duty. Fundasaun Mahein sees a positive development within PNTL in the promotion of community policing through the Ofisia Policia Suku (OPS) program. Police forces are now stationed in all 65 administrative offices (formerly sub-districts). Unarmed police work with communities to prevent crime and address issues in a non-confrontational manner. The program is well received by the communities.